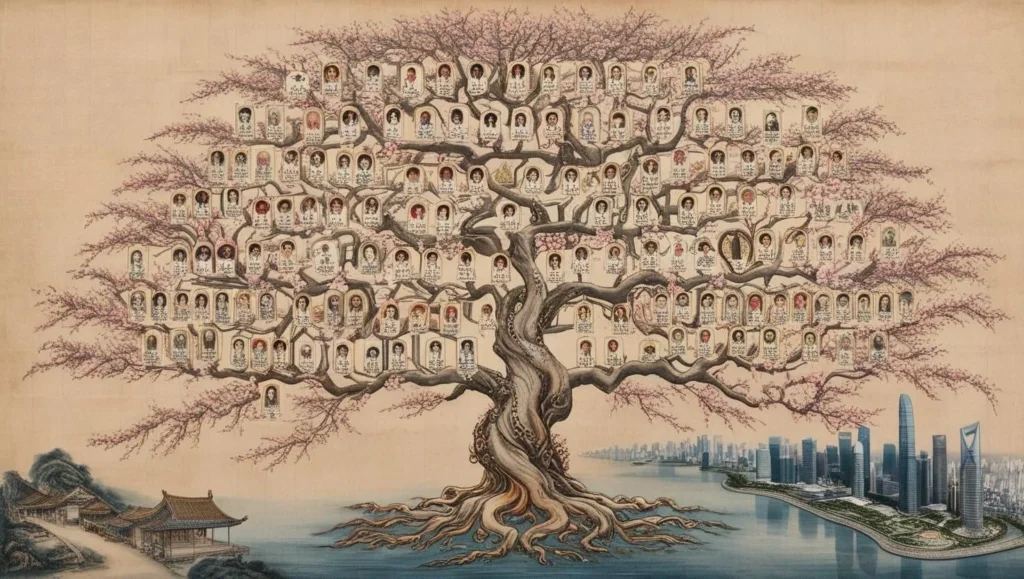

Dating back over a millennium, these meticulously maintained documents chronicle not just names and dates, but entire family histories, migrations, achievements, and moral teachings. Passed down through generations, these “books of life” connect modern Chinese individuals to their ancestors through unbroken chains of documentation, serving as bridges between past and present.

Beyond mere historical accounting, these genealogical records function as repositories of cultural values, ethical standards, and collective identity that have shaped Chinese society for centuries.

Zupu vs Jiapu

The terms zupu and jiapu, while often used interchangeably by casual observers, actually represent different scopes and purposes in Chinese genealogical tradition.

Zupu (族谱) translates literally as “clan genealogy” and encompasses the broader, more comprehensive record of an entire clan or lineage group sharing the same surname. These extensive volumes often trace back to a common ancestor many generations removed and include multiple family branches across different regions.

Jiapu (家谱), on the other hand, means “family genealogy” and typically focuses on a single family unit or household’s direct line of descent. More intimate in scale, jiapu records tend to contain more detailed personal information about recent generations and are primarily maintained for immediate family members rather than the extended clan.

This distinction reflects the layered structure of traditional Chinese society, where one’s identity was defined by both immediate family connections and broader clan affiliations.

Reading the Zupu

For modern readers, particularly those unfamiliar with classical Chinese writings, an immediate challenge in approaching these documents is their traditional format.

Both zupu and jiapu are almost invariably written in classical or literary Chinese using traditional characters (繁體字), not simplified ones, and follow the traditional reading pattern of vertical columns read from right to left—a stark contrast to contemporary Chinese documents and certainly to Western reading habits.

This traditional format reflects these documents’ historical continuity and reverence for ancestral conventions, but can present a significant barrier to accessibility for those without specialized training.

Navigating the complex structure of a traditional zupu requires understanding its unique organizational logic and symbolic language.

Traditional zupu typically begin with an introductory section containing prefaces (序), clan rules (族规), and often a laudatory biography of the founding ancestor.

The core genealogical information follows a patrilineal structure, organised by generation rather than chronology, with each generation (世/代) marked and numbered.

Male descendants are recorded with their birth dates (often in the traditional Chinese calendar), achievements, marriages, official positions, and burial locations.

Women appear primarily as wives, with entries noting their natal family surname, occasionally their father’s name, and sometimes their burial information. Even in my family’s Zupu, daughters were not recorded.

The text employs specialised terminology for relationships and life events, with symbols and notations indicating status distinctions like scholarly achievements or government service.

Most crucially, readers must understand the horizontal and vertical axes of organisation: horizontally tracking siblings and cousins within the same generation, and vertically following the direct line of descent across generations. Modern readers often create charts or diagrams to visualise these complex relationships when consulting historical zupu.

Where is my Zupu?

For those curious about their ancestral roots, finding one’s family zupu in the modern era involves a blend of traditional approaches and contemporary resources.

The search typically begins with family connections—consulting elderly relatives who might possess physical copies or know which branch of the family maintains the records.

Ancestral villages and hometown clan associations (宗亲会) remain vital repositories of genealogical information, with many still maintaining ancestral halls (祠堂) where historical records are preserved.

Chinese diaspora communities have established genealogical societies that assist members in tracing their roots. For those in the diaspora who may have lost direct connections to their ancestral homeland, these resources offer promising pathways to reconnect with their heritage through these invaluable historical records.

The purpose of this website is to share my personal journey of discovery and shares my insights along the way that might help others. A personal page from my family Zupu can be found here.